Coast Guard Memories

by Art Dobney

In this undated document, Art Dobney (1915-1996) shares his memories of Coast Guard experiences in the Bandon area.

"When the station was built, it was designed to fit over the old boathouse. When the [1936] fire burned, our station was on the hill, and the boathouse with three boats was right there. It burned, only the tracks and ramp were left. So they built the new station right over that place and incorporated the tracks and ramps.

We had three boats, a 36 footer life boat, our big boat. And we had an open motor surf boat , which was a 30 foot boat; also we had a pulling boat which held 8 people.

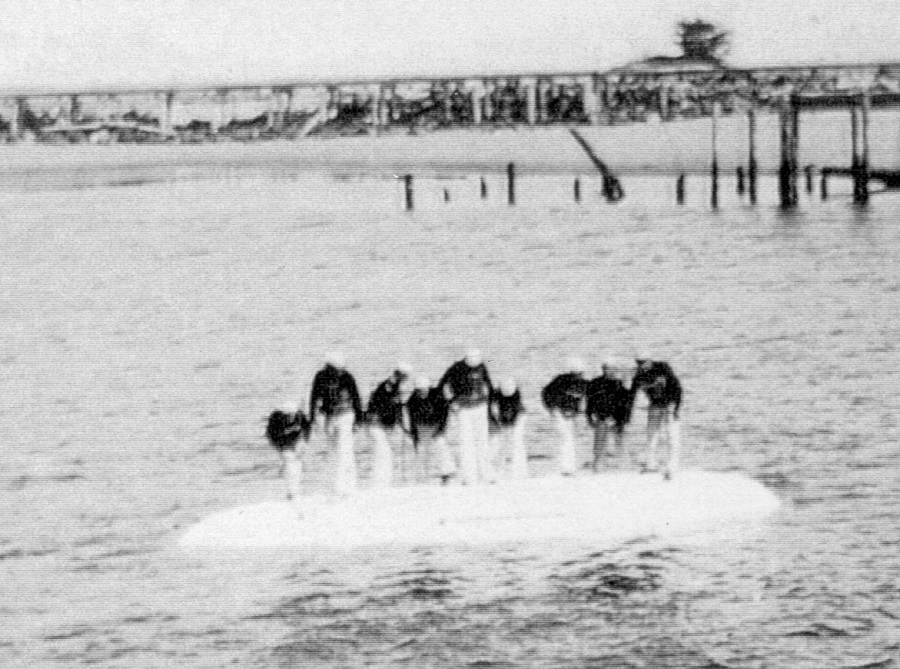

Talk about drills! We’d take that boat and execute drills every day. There was not a day that went by that we didn’t have some sort of a drill. Boat drills, sail drills, all kinds of drills. But there was one thing I had to do most, and that was taking a pulling boat, with 8 men and a coxswain, go on out, pulling oars and everything, and do capsize drill, 8 to 10 times: capsize, then bring it back up. Lash it then bring it back home. We were young then! No, we weren’t lashed in! I was an open boat, rowboat, eight people and me, the coxswain in the back, with the sweep or rudder. The sweep was 20 feet long. You have seen the boats in Venice in the canals and the man in the back of the boat, that’s me. Eight guys rowing, and I gave them the stroke, and they would pull away together, weigh the oars. That was one of our drills. The reason for this drill is, in case of emergency and the boat does capsize, you will know what to do, get out from under it, pull yourself up with the boat. The way you do it is: eight men and one at the back, you ship all the oars, secure them, everything that is loose is lashed down. The boats righting lines are coiled by each man, fourteen-fifteen ft. line with a float on it coiled right beside him on the floor. On the side of the boat at the lifelines; they are the lines that are looped out there. When they come back to the boat, you must get a hold of them.

You capsize the boat, either

starboard or portside,

either one. You say: “Man the starboard side (or port side) and everyone

steps

to the starboard side, (it is the opposite righting line) and lean back

and

overturn the boat. And as that gunnel comes over, put yourself away from

the

boat; it comes over, belly up, coxswain sitting on top and rest of the

men in

the water. Coxswain gives the order to right the boat and they walk

right up

the side of the boat and pull it up right over. I say “How do you feel,

fellas,

let’s do it again,” … Another drill was the life boat drill, and then we

had

the Lyle drill, where we shoot the projectile over the top. … We would

shoot

the projectile across the river, then we would bring the man in. That is

the

breeches buoy drill, the Lyle drill. You shoot the 12 pound projectile,

had a

flat laid line about as wide as my finger; flat woven flax linen line,

500

yards of it in a box called a “faking box.” The box had fingers in it,

that

that line is fixed in that box so it will run out. The box has a top on

it.

So—you put the faking box down here, make the projectile fast, It is

stainless

steel and looks like a rolling pin with a little neck on it with a ring.

You

make a line fast to that, put the powder in the gun; on the back of the

gun is

the cap. The gun is then capped. The I would say “Stand clear,” “fire!”

and

that line would shoot straight across the river! That line goes out, a

man goes

up the mast. You must get to the yardarms or you have to do it all

again,

otherwise you couldn’t get the lines. So, the man gets up on the crows

nest and

makes the hawser fast, pull it fast around the mast. We send the

breeches buoy

up to it; you try to do it in five minutes, four minutes; all stations

did it.

You capsize the boat, either

starboard or portside,

either one. You say: “Man the starboard side (or port side) and everyone

steps

to the starboard side, (it is the opposite righting line) and lean back

and

overturn the boat. And as that gunnel comes over, put yourself away from

the

boat; it comes over, belly up, coxswain sitting on top and rest of the

men in

the water. Coxswain gives the order to right the boat and they walk

right up

the side of the boat and pull it up right over. I say “How do you feel,

fellas,

let’s do it again,” … Another drill was the life boat drill, and then we

had

the Lyle drill, where we shoot the projectile over the top. … We would

shoot

the projectile across the river, then we would bring the man in. That is

the

breeches buoy drill, the Lyle drill. You shoot the 12 pound projectile,

had a

flat laid line about as wide as my finger; flat woven flax linen line,

500

yards of it in a box called a “faking box.” The box had fingers in it,

that

that line is fixed in that box so it will run out. The box has a top on

it.

So—you put the faking box down here, make the projectile fast, It is

stainless

steel and looks like a rolling pin with a little neck on it with a ring.

You

make a line fast to that, put the powder in the gun; on the back of the

gun is

the cap. The gun is then capped. The I would say “Stand clear,” “fire!”

and

that line would shoot straight across the river! That line goes out, a

man goes

up the mast. You must get to the yardarms or you have to do it all

again,

otherwise you couldn’t get the lines. So, the man gets up on the crows

nest and

makes the hawser fast, pull it fast around the mast. We send the

breeches buoy

up to it; you try to do it in five minutes, four minutes; all stations

did it.

The only time I used the breeches buoy was on the wreck of the

Alvarado, off Horsfall beach when she wrecked up  there.

We used it to get the people off. That was in 1943, I think; the war

with Japan was still going on. …Our station was placed in charge of

the rescue and we took everything up there. We had our boat, motorboat

with a trailer. I took it and the Coast Guard crew to Junction City

when they had that terrible flood there. Well, we took our boat up to

Horsfall beach along with the other stations; pretty bad wreck. Lumber

ship, Moore Mill owned it . They owned two ships, the Port of Bandon

and the Alvarado. The Navy came down and took them both, and the

Alvarado became a supply ship. All the years she ran under Captain

Jacob Christianson, she never had any trouble at all. Soon as the Navy

got it, they wrecked it at Horsfall beach. No one got hurt, got

everyone off safely. She didn’t hit the rocks, just came up on the

beach like a big house. The only thing was just getting the people off

without getting hurt. No immediate danger; the surf was breaking over

the stern pretty bad, but it was not that terrible. It happened at

night.

there.

We used it to get the people off. That was in 1943, I think; the war

with Japan was still going on. …Our station was placed in charge of

the rescue and we took everything up there. We had our boat, motorboat

with a trailer. I took it and the Coast Guard crew to Junction City

when they had that terrible flood there. Well, we took our boat up to

Horsfall beach along with the other stations; pretty bad wreck. Lumber

ship, Moore Mill owned it . They owned two ships, the Port of Bandon

and the Alvarado. The Navy came down and took them both, and the

Alvarado became a supply ship. All the years she ran under Captain

Jacob Christianson, she never had any trouble at all. Soon as the Navy

got it, they wrecked it at Horsfall beach. No one got hurt, got

everyone off safely. She didn’t hit the rocks, just came up on the

beach like a big house. The only thing was just getting the people off

without getting hurt. No immediate danger; the surf was breaking over

the stern pretty bad, but it was not that terrible. It happened at

night.

This port was quite busy. I would saw that we would have 20 calls a months, as high as forty calls in the summer months; calls for assistance of some type. Lots of sport fishing calls. I took quite a few commercial fishermen calls—can’t tell you how many. We had a lot of urgent calls, like one time on October. We had our lookout on the beach (right where the restroom is now), we had a steel tower there. No road out there; there was a trestle walkway out to there. On night, the lookout called in the middle of the night. There was flares out to sea. It was a nasty night, an awful night. I lost the windshield off the boat getting out. We got out there just getting daylight, 40 miles out, soaking wet. It was a Chinese New Year celebration! We had other calls like that. We got back to the bar late that next afternoon, couldn’t get in, went to Coos Bay, or Port Orford, couldn’t get in anywhere, low on fuel So I tied up at the “whistler” out there and rode her out. We were out there four days, and that was all for nothing. But—we had those kinds of calls.

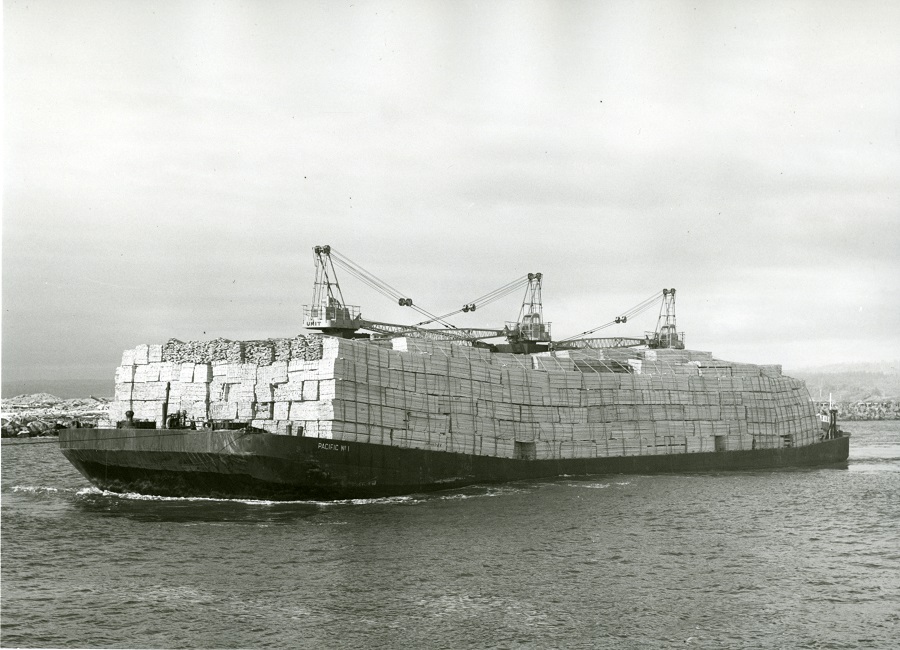

In those days there was an awful lot of coastwise lumber shipping. They had lumber schooners. We got all the Schaeffer boats: Margaret Schaeffer, Anne Schaeffer, all the Schaeffer boats came in here for the mill. The Oliver boats too. One, the Oliver, is still out there in the North Jetty- the Oliver, the Barbara, all the Olson boats came in here. There were no tugs or barges here. The Schaeffer boats carried the most lumber; they were the largest. I can’t remember the date really, but it was all before the war. I can remember when the Bandon band and everybody got out on the jetty; they were having a big celebration because the Anne Schaeffer was taking a million board feet of lumber and that wasn’t heard of before. All the flags and all the people and there went the “Anna” with those million board feet of lumber. There were twenty-thirty men on one of those boats. The lumber was all coastwise to San Pedro, mostly for shipment overseas; or Seattle for shipment up to midway etc. This coast was busy with those schooners. Moore Mill with two of their own going all the time; they had schedules. This was before the war, before the Coast Guard building was built.

When

I came back, the barge business was starting. One barge can take four-

five million feet of lumber with four- five men on a tug. Compare that

with the schooner carrying one million board feet and twenty- thirty

men! So- the barges eliminated the schooners which were getting old,

of course. I have seen five ships in here at once and they were all

taking on lumber. You have pictures of some of them here in the

museum. Think of that: one barge taking four-five million feet of

lumber; they just eliminated the old schooners, the old ships. The

ships would come every week or ten days; it was 27 days round trip

from San Francisco to here; a barge would take five times as much and

do it faster. This was a big change point for the lumber schooners and

they were put out of business. As a result then, our life saving

activities went “down the tubes”. Then the building came. Talk about a

lot of activity on the river! Some sources say it was 1890 when the

site was bought.

When

I came back, the barge business was starting. One barge can take four-

five million feet of lumber with four- five men on a tug. Compare that

with the schooner carrying one million board feet and twenty- thirty

men! So- the barges eliminated the schooners which were getting old,

of course. I have seen five ships in here at once and they were all

taking on lumber. You have pictures of some of them here in the

museum. Think of that: one barge taking four-five million feet of

lumber; they just eliminated the old schooners, the old ships. The

ships would come every week or ten days; it was 27 days round trip

from San Francisco to here; a barge would take five times as much and

do it faster. This was a big change point for the lumber schooners and

they were put out of business. As a result then, our life saving

activities went “down the tubes”. Then the building came. Talk about a

lot of activity on the river! Some sources say it was 1890 when the

site was bought.

Another thing: There was a big fish plant here and our commercial fishing was quite active then. There were at least twenty fishing boats which went out of Bandon. They were working through the winter and the spring; there were fish buyers here. And we had a canner up the river- a big cannery. Commercial fishing didn’t slow down at all, and they extended the North Jetty, and that gave us a better bar. We did well there up to 1946, quite a big fleet. There wasn’t the large sport fishing as now. We got a lot of calls from the sport fishermen because they were so inadequate little open boats and the pitiful little motor on the back; they weren’t nearly as nice as the boats they have now. We pulled in a lot of people.

In this building, the Coast Guard building, in the kitchen galley area or third-class cooks. The kitchen is called the galley. You know the boat room? With the three boats in it? You walk in, there is a little shower in a clean room with a deep sink for the cooks to clean vegetables etc. Right around the corner was the galley, two cooks worked in there all the time, did their own baking, everything. Then the mess hall was right there; had two tables in there. We had single people and we had married people. Married people were allowed to go home when not on duty. Where they lived was called “Little America”, all little houses. I built that first little house next to the station, my first cabin. Down the street another little house, a guy got married. Eight houses, the Coast Guard built in their spare time. There wasn’t a house on the street at first, except the old Brewer Building. The single men messed in the building; slept upstairs, ate in the dining hall; the married men ate at home. There were only 8-10 people who lived in the Coast Guard; but when other people had duty, night duty, they had to come to the station and go home the next day. The cooks work 24 hours on, 24 hours off; always someone on watch. Watches going all the time. The watch was in the tower on the South Jetty, big steel tower out there, right where it is today. There is a dead end road behind the hospital, where they used to have a watch tower there too. They took the tower off the beach because of weather conditions and put it up on the hill behind where the hospital is now. We also had an auxiliary power plant there; when the lights went out the plant would kick in, but that was after I left. The main watch tower was on the beach when I was here.

Now- the little room across from the mess room was called the “ready” room. When you came off your watch, you did whatever you had to do in there, checked your clock, went over to the office, put your clock right in the locker by the office door, put your time clock and transcript in the locker. It was just a little radio room.

The big room was a day room, with a pool table, writing desks etc. No partition then in that room. Three bedrooms up there. Those three rooms on the end were NCO rooms; three people: Chief machinist mate, my number 1 and chief steward. Those quarters were a little bit nicer than the others. Their access was on the other end of the hall. The stairway goes down to the office. We had 118 men; we used the attic, we usually had men sleeping up there. We had carpenters come and build [missing section]. The whole upstairs was sleeping quarters except our end was never finished. Twenty-four men slept up there.

Horses: It took a lot of manpower to maintain the animals. It was like preventive maintenance. You know if you see a police officer walking around it is a deterrent to crime. We had a perimeter of defense around the whole U.S.; an aggressor knew we were alert, that we had an alert line. Now, it is all automatic, as the Dew Line, which eliminates the manpower, as a deterrent. Mostly it was a deterrent during World War II; as far as heroics go, there weren’t any, but just let it be known that we were alert.

Routine: Just an ordinary day: “Colors” at 8 o’clock. Everyone but the cook stands “colors”. We had our Lanyard colors just outside where the garage doors are, a great big flag pole. I would be out there and here comes the crew; we would all line up with our backs to the garage, facing the colors. The number 1 is the foreman who runs the crew; I run the office, the daily log, report, etc. The number 1 stays out there and gives assignments: “Now, Jones, you and Peterson go out and mow the lawn.” He gives the work schedule. We work until noon, then lunch until one o’clock. There is a drill for the day, breeches buoy drill etc.- we had a rifle range out there, (had to keep the people on top) and we had so much rifle range practice. It was right where Sunset Motel is now. Rifle range, big butts and everything out there, 500-yard range. We went up by jeep. We did competitive things with other stations too: we had shoot-offs, our best men, their best men. We would also take our boats and row against each other. We would have a breeches buoy drill and another station takes their crew to participate. I go down; they all know what to do. All I do is make sure the gun is all roper. Then he says,” All ready”, and all stand back and-Bam! It goes off, the line goes out. After one of these drills, the line is all out. We have to put all the gear back together. By that time, it is probably 4 o’clock. At 4:30 the active day stops; just as “watches” go. This happen every day. The big day is Friday, which is clean-up day. Everything is scrubbed and then inspection. I go round and inspect everything. Every Friday, on every station it’s the same thing, clean up the area, ever thing in the area, then inspection. Saturday and Sunday are days off, whoever didn’t have watch could go on Liberty. We had “port” and “sta’board liberties. Our crew had ten men, five on “port” and five on “sta’board”. Had to keep a certain number there for emergencies, of course. Everybody else had Liberty. If one Saturday you had “port”, next Saturday you had “sta’board”. Always figure one man in the hospital or a man on leave so if a crew is ten you have to have twelve. You are always short. One man gone every month on leave. I never got a month vacation, someone would have to come from another station. A “watch” is four hours on; twenty-four hours duty with on and off time but you are there on duty with four hours on watch. Say you have 8-12 o’clock watch, so you get a boat call at midnight after you just got in. Well, you hit the deck too; you were sleeping but you hit the deck too. In Coast Guard you do everything: carpenter, painter, electrician, and you also have to know how to handle a boat.

I was here when this building was built. I built the house next to this coast guard building; my house is the green house.

Quinn Construction Co. built this building. Head supervisor was Bob Davis, wonderful man. It was two years in the building of it. Bob Davis became a good friend of mine. He came down from Seattle with Quinn Construction Co. He liked it so well, he built a house on Bear Creek and stayed here. I was only 21-22 years old and he helped me build my house. My house was the first house on the street. My house was built right over The Gallier Hotel. When we got here, all there was, was what had been in the hotel, all burned, all the rubble left. Beds, silverware, all rubble. The fire trucks in the street all burned out. This was September 1936. I built my house in January and February 1937. We dug up the old drain pipes and everything, and used them. We helped each other, knocked all the dirt off. We used all that building our houses. Across the street, where the little house is now tucked into the hill, there used to be a great big house, across the street from the station. All that was left after the fire was a big fireplace. I hooked a line around that enormous fireplace and pulled it down.